Piloting No-Dig Lead Pipe Detection Technologies: Lessons Learned from the Field

Developing practical, field-tested solutions that identify unknown pipe materials with minimal resident disruption is essential for delivering a smoother, faster, and more reliable program. DC Water partnered with the Lead Free Group, a joint venture between CDM Smith and Ramboll, to pilot no-dig alternatives to test pitting that could support their mission to identify and replace lead pipes.

bridging the gap: innovation and practical results

In many communities, identifying LSLs still depends on outdated records. Predictive modeling and digital inventories help narrow the search, but they require accurate field data. Field verifications can be intrusive, costly, and coordination-heavy for utilities and residents alike.

Conditions vary widely across communities. Factors like infrastructure age and local or state building regulations all play a role, so a method that works in one distribution system may not work for another. That's why DC Water pilot tested detection technologies against traditional and reliable test pit methods under real-world urban conditions. The goal: determine the best mix of approaches to reduce unknowns.

how did they do it?

The team tested two no-dig detection technologies at 43 homes: Technology 1 uses external ground probes, and Technology 2 inserts a probe into the pipe at the water meter. Both tools detect pipe materials through electrical properties. Test pits on the private and public sides of each property were used to confirm results using the industry-standard method of excavation.

The pilot assessed each detection technology using five main criteria: accuracy, reliability, ease of deployment, labor required and cost. Accuracy was key. Could the tool consistently and correctly identify pipe materials as reliably as test pitting? The team also looked at why a tool might fail (e.g., plumbing or soil conditions), how much effort it required compared to a test pit, and whether it could deliver cost savings over test pitting.

- Technology 1’s method involved placing electrodes along the service line to measure conductivity, with reports delivered in 72 hours. This platform is still in the pilot phase.

- Technology 2 used probes inserted at the water meter to gather real-time data, with near-instant reports. This platform is commercially available. For this pilot, two different style probes were used at different locations depending on the pipe configuration.

Ultimately, 43 properties were selected for testing; however, only 38 properties were verified with test pits due to limited customer participation at five of the tested properties. Test pits were excavated at two locations: a 36–48 inch hole at the water meter pit and an 18–24 inch hole at the property line.

pipe access

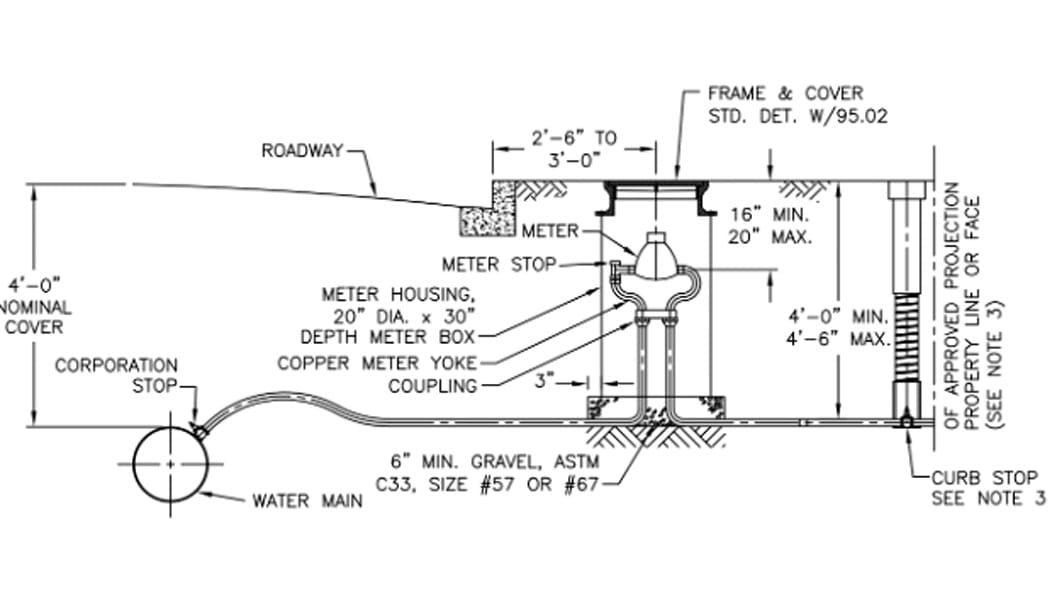

A key challenge with physical service line identification is obtaining access to the pipe. In the test area, a typical service connection includes a meter housed within a buffalo box, connected to a riser that leads to the service line (Figure 1). Service lines in the test area ranged from ¾-inch to 1-inch in diameter.

Figure 1 Typical Service Connection in DC Test Area (Source: DC Water)

Figure 1 Typical Service Connection in DC Test Area (Source: DC Water)

Overall, Technology 1 tested both the private (meter to house) and public (main to meter) service lines at 40 of the 43 sites, while Technology 2 was able to test 24 public-side and 29 private-side service lines. The Technology 1 system only needed direct access to the water meter and was unable to test service lines at three of 43 sites due to obstructed or inaccessible meter pits.

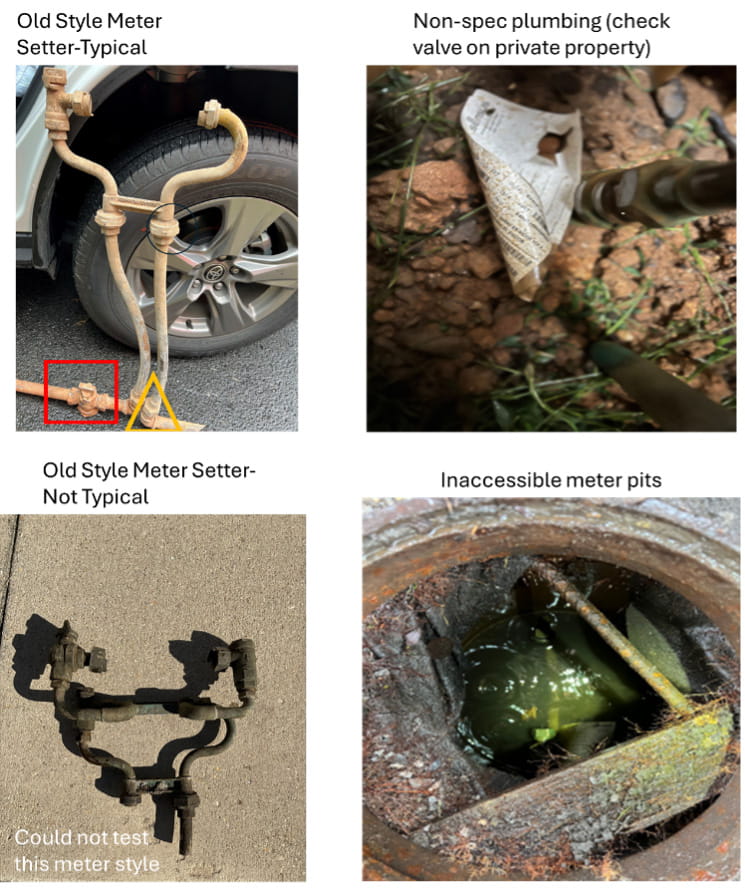

In contrast, access challenges had a greater impact on Technology 2 since its probe needed to be inserted directly into the pipe for testing. Technology 2 could not be used at six properties due to obstructed or inaccessible meter pits, meters in poor condition that posed a risk of damage if removed, pipes that were crimped or severely corroded, or severe bends that the probe could not navigate. An additional five private-side and 10 public-side service lines could not be tested with Technology 2 for the same reasons although it was able to test and provide results for the other side of the service line. During testing, previously unknown ½-inch check valves were discovered at two properties, and one property had an older meter type that DC Water was not aware of and therefore could not be tested (Figure 2). Some meter risers were only ½-inch, which made them challenging for Technology 2 to navigate through. Two sites withdrew from Technology 2 testing due to the need for a water shutoff. No material results were provided for these locations.

Figure 2 Examples of Challenging Plumbing Configurations Encountered

finding lead service lines

After removing the pipes that were not accessible, a total of 40 properties were evaluated with service line materials provided by Technology 1 and 30 properties were evaluated with service line materials (for at least one side) provided by Technology 2.

The most critical measure of any service line identification technology is accuracy: can it reliably detect lead pipes? The last thing any public utility wants to do is label a lead pipe as a non-lead material and not offer a replacement at that address or provide a false sense of security to the residents. Technology 1 initially reported 13 LSLs among the 40 properties tested, with the remainder identified as non-lead. Technology 2 initially reported identifying zero LSLs across the properties it tested. Since neither technology had been proven in DC Water's system and results hadn't yet been confirmed through test pitting, DC Water provided filters to all properties reported as non-lead as a precaution.

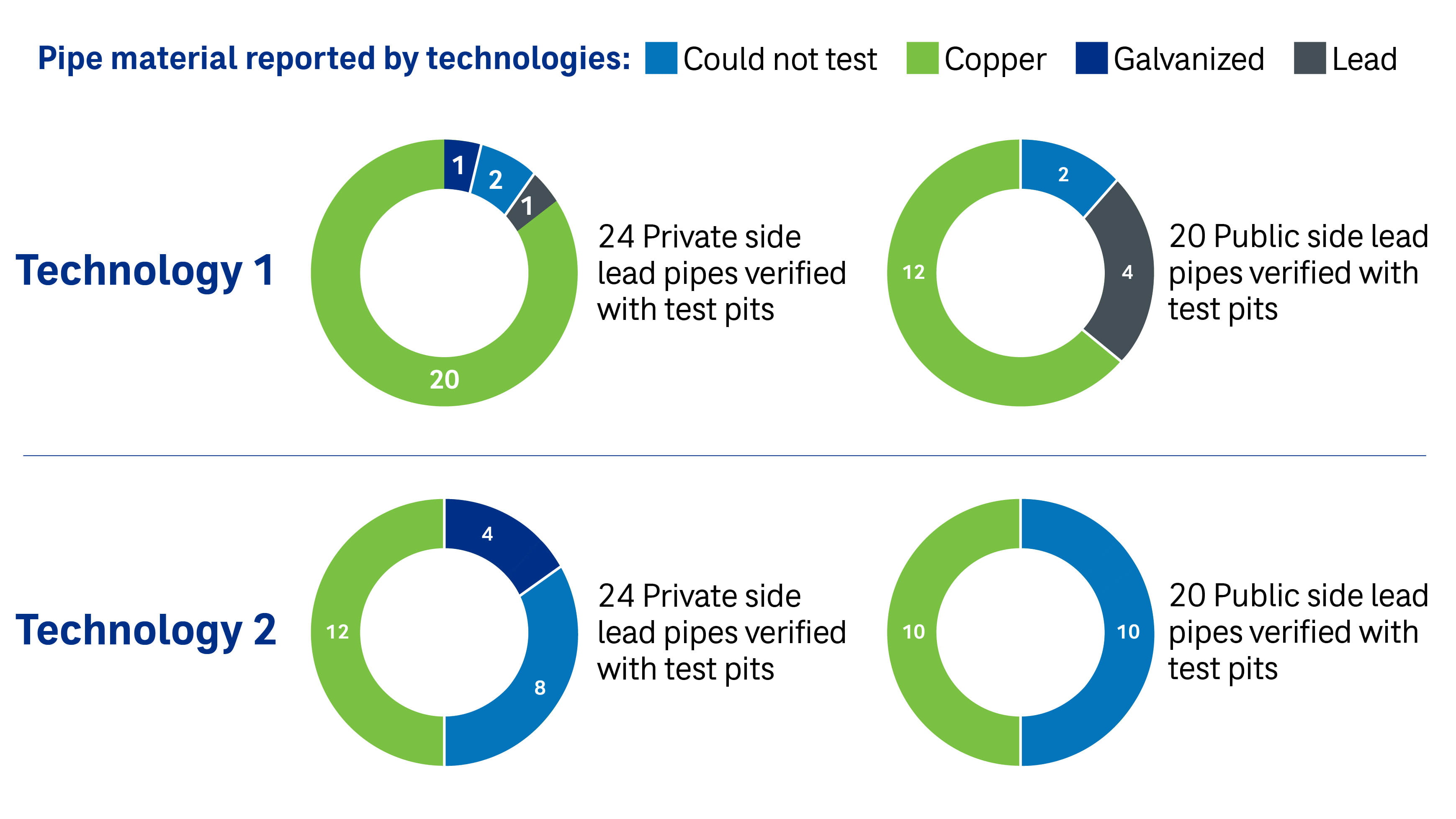

Test pits followed the testing of the new technologies and confirmed 27 properties (of the 38 confirmed with test pits) had LSLs: 24 on the private side, 20 on the public side. Although several of these LSLs were at properties where results were not provided by Technology 1 and/or Technology 2, many were incorrectly identified as non-lead through the pilot testing. Figure 3 summarizes the service line materials identified with Technology 1 and Technology 2 compared with the test pit results.

As shown, Technology 1 correctly identified one of the 22 private-side lead pipes and four of 20 public-side lead pipes it tested. Technology 2 failed to identify any of the 16 private-side or 10 public-side lead pipes it tested. The lead swab Technology 2 used as secondary confirmation also returned no lead result at these locations.

Figure 3 Summary of Service Line Materials Identified with Technology 1 and Technology 2 Where the Test Pits Found Lead Pipes

The performance of both of these technologies raised questions about their accuracy in DC Water's system. Both technologies performed well below what's needed for reliable material identification.

Technology 2 faced plumbing configuration challenges that may have compromised its effectiveness. Some meter risers contained unexpected ½-inch piping between the meter and service line, creating bottlenecks the probe may have struggled to pass through with the equipment Technology 2 provided for the pilot. Technology 2 reported many lines were ½-inch based on their inspections, but test pit measurements reported the service lines were ¾-inch to 1-inch.

To address the plumbing configuration issues, the team analyzed results where Technology 2 reported inspection lengths exceeding 4.5 feet, where the probe would be past the riser and within the service line itself. Even then, Technology 2 failed to identify any lead pipes. The tool reported inspecting between 4.6 and 20 feet at 13 of 16 private-side lead pipes and between 4.6 and 11 feet at six of 10 public-side lead pipes. None of them resulted in a determination of “lead” from the Technology 2 tools used in this pilot.

These results highlight the importance of testing technologies in context: what works for one utility may not work for another. The results of this pilot are specific to DC Water’s distribution system. In other systems, these technologies may perform more accurately, and Technology 2 may be able to access a greater number of service lines to categorize materials. However, the configuration and size of the piping in DC clearly limited the effectiveness of Technology 2 in this pilot. The chart below shows why DC ultimately decided to continue using test pits for the time being.

| Factor | Test Pit (Current method) | Technology 1 | Technology 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utility Considerations | Identification Method | Visual | Electrical | Electrical (Probe) and Chemical (Swab) |

| Cost per Address in Pilot (average) | $1,700 to $2,400 1 | $650 1 | $2,000 1, 2 | |

| Onsite Time (minutes, average) | 180 to 360 3 | 91 | 51 | |

| Accuracy of LSL Identification in DC Water's System | High | Low | Low | |

| Impact on Residents and the Community | Level of Coordination with Resident | High | Low | Medium |

| Water Service Impacted | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Service Line Disturbance | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Traffic Flow Disturbance | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Restoration Required | Yes | No | No |

Note:

- Cost in 2024 dollars

- Based on costs to conduct the small pilot study. Costs to implement in other areas will vary by number of homes surveyed and local conditions.

- Based on interviews with Lead Free DC construction inspectors

putting homeowners first

Earning residents’ trust is essential when requesting access to perform work on private property. Protective measures were also a top priority. To maintain confidence and safety, every household received NSF 53/42 certified filters and flushing instructions to make sure drinking water remained safe throughout the process and afterwards. Once a lead pipe was identified, crews took steps to remove the pipe as soon as practical to help safeguard water quality, and the team worked closely with residents to minimize the time between identifying an LSL and replacing it.

efficiency and clarity guided every stage of this pilot

Prior to the field work:

- The team focused pilot sites in areas with active test pit and LSL replacement contracts to minimize delays in starting verification work and replacements.

- Households benefited from clear timelines and the peace of mind that replacement would follow quickly.

During the field work:

- The team kept constant communication with the residents during the testing process by engaging them at the start of testing and walking them through the process.

Within a few weeks after the field work:

- Crews started test pit verifications and replacements to identify and remove LSLs as soon as practical.

- The Lead Free Group shared key takeaways from the pilot to refine processes for future testing of alternate identification methods.

the essential role of test pits

While new detection tools show promise in many systems, DC Water’s pilot highlighted that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to getting the lead out—each utility has unique needs. Urban systems are often complicated, full of undocumented repairs and pipe configurations that these new detection methods may not be able to accommodate. In DC Water’s case, test pits provide the confidence to act on solid data, protect public health, and focus resources where they’ll have the greatest impact. DC Water plans to continue to pilot new technologies and reduce the number of test pits needed for completing the service line inventory and removing all LSLs in the system.

Every project is unique and has its own set of challenges. It’s critical to work closely with our clients to make sure we are delivering what they need.

This pilot highlighted that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to getting the lead out. Each utility has unique needs.