6 Major Takeaways from PFOA/PFOS CERCLA Designation

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has released the much-anticipated final rule to add two long-chain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)—along with their salts and structural isomers, to the Superfund program under section 102(a) of Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). The designation as CERCLA hazardous substances allows EPA to use it’s authorities for:

- notification of PFOA/PFOS releases under CERCLA section 103;

- response actions (e.g., removal or remediation) under section 104;

- enforcement actions under section 106; and

- cost recovery under section 107.

- Current and former owners and operators of facilities manufacturing or using PFOA and/or PFOS, including:

- Importers and importers of articles

- PFOA and/or PFOS processors

- Waste management and and disposal facilities

- Hazardous substance transport to disposal or treatment facilities

Polluters are liable for response costs, natural resource damages and assessment costs and costs pertaining to certain health assessment or health effects studies.

“A CERCLA designation gives EPA or other agencies authority to require facilities to investigate and report PFOA and PFOS releases and to enforce cleanup of a contaminated site or to recover costs in doing so, the classic ‘polluter pays,’” said Tamzen Macbeth, CDM Smith environmental engineer and remediation practice leader. "It has broad implications requiring investigation and remediation of sites, including re-opening closed sites, with overall costs likely in the billions of dollars.”

Now that EPA has published the Rule in the Federal Register, CDM Smith’s team of PFAS experts have noted the following takeaways:

1. New reporting and transportation requirements

The EPA explained that CERCLA hazardous substance designations have certain direct effects. The first direct effect requires anyone in charge of a vessel or an offshore or onshore facility to immediately report any release of such substances at or above the reportable quantity (RQ) to the Federal, state, tribal and local authorities (CERCLA section 103(a), Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) section 304).

The rule sets a default reportable quantity (RQ) at a 1.0 lb release in a 24-hour period. That may not be an issue for most facilities that process drinking water and wastewater. Plants with flows in the 10-100 MGD range, for example, could discharge between 1,200 and 12,000 ng/L of PFOS/PFOA and still be under the RQ.

However, experts warn that the PFAS contained in the spent media waste from water treatment technologies like granular activated carbon and anion exchange resins could still trigger a response. “With granular activated carbon or anion exchange resins, you will be accumulating PFAS,” says Mark White, CDM Smith vice president and drinking water practice leader. “Depending upon the water quality and operating conditions, a utility could be producing enough PFAS to require reporting. over the course of a few months or a year.”

The second direct effect requires federal agencies to meet the property transfer requirements in CERCLA section 102(h). This includes "providing notice of when any hazardous substances 'was stored for one year or more, known to have been released, or disposed of’ and covenants concerning the remediation of such hazardous substances in certain circumstances.'"

The third direct effect requires that substances designated as hazardous under CERCLA be listed and regulated as hazardous materials by the US Department of Transportation under the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act, pursuant to CERCLA section 306(a).

[A CERCLA designation] has broad implications requiring investigation and remediation of sites, including re-opening closed sites, with overall costs likely in the billions of dollars.

2. No exemptions for any industry, but enforcement will prioritize “Major PRPs” and accompanying memo provides EPA approach on enforcement.

The EPA did not include formal exemptions in the final CERCLA rule, but they did release a separate CERCLA enforcement discretion policy memo. The EPA has well-established enforcement discretion policies that provide liability protections to parties in certain circumstances, such as innocent landowners, de micromis parties, residential property owners at or near Superfund sites, and contiguous property owners. The memorandum provides information about how EPA will exercise its enforcement discretion under the CERCLA concerning PFAS. In it, the EPA emphasizes that “the rule does not change the statute’s liability framework, which provides liability protections in certain circumstances for parties that are not primarily responsible.” The memorandum directs EPA enforcement and compliance to focus on holding responsible entities considered “major principal responsible parties (PRPs)” who significantly contributed to releasing PFAS contamination into the environment, including:

- Parties that have manufactured PFAS or used PFAS in the manufacturing process;

- Federal facilities; and

- Other industrial parties.

The EPA policy also clarifies that they do not intend to pursue entities where equitable factors do not support enforcement against them for PFAS actions or costs under CERCLA, including (but not limited to):

- community water systems and publicly owned treatment works (POTWs)

- municipal separate storm sewer systems (MS4s)

- publicly owned/operated municipal solid waste landfills

- publicly owned airports

- local fire departments

- farms where biosolids are land-applied

The EPA will also help protect these entities from litigation risk that may arise from other PRPs attempting to recover costs for PFAS cleanup by:

- EPA seeking to require those PRPs to waive their rights to sue parties that meet the equitable factors

- EPA entering settlements with concerned parties under statutory authority to help mitigate litigation risks and associated costs to protect parties that meet the equitable factors from CERCLA claims by other PRPs.

This Policy does not exempt parties from reporting PFAS releases under CERCLA. In addition, the guidance does not alter the EPA’s policy of not providing no-action assurances outside the framework of a legal settlement, and the EPA will evaluate each request for relief under this policy based on all available information.

Depending upon the water quality and operating conditions, a utility could be producing enough PFAS to require reporting. over the course of a few months or a year.

3. Increasing the number of National Priority Sites.

Once a Federal agency learns of a release or potential threat of a release of a hazardous substance, pollutant and/or contaminant, CERCLA authorizes response in one of three ways: by determining no action at the Federal level is warranted; by undertaking a removal action (if the situation presents a more immediate threat); or by assessing the relative risk of the release to other releases via the NPL [National Priorities List] listing process that is the first step towards a longer-term remedial action.

The Superfund process has several different outcomes, beginning with a preliminary assessment and/or site inspection. Not all sites that initially trigger a response will be added to the NPL. According to the EPA, only about 3% of assessed sites have been placed on the Superfund list.

“This program typically addresses our most contaminated and hazardous sites,” said Macbeth. “It’s not a foregone conclusion that one of these sites, because they’re releasing PFAS, is going to become a Superfund site.”

The new rule is also expected to affect existing and even closed Superfund sites. For existing Superfund sites nearing closure, the designation could push back the timeline of remediation projects, add significant costs, and require new treatment technologies. According to Macbeth, the new reporting requirements could also lead to the reopening of previously closed sites as part of the CERCLA 5-year review process.

4. Prepare for potential liability and lobbying for protections for public utilities.

EPA and delegated agencies could recover PFOA and PFOS cleanup costs from potentially responsible parties, to facilitate having polluters and other potentially responsible parties, rather than taxpayers, paying for these cleanups.

Based on current action, water and wastewater utilities are not exempt from liability. Advocacy groups are continuing to lobby to protect water and wastewater processing facilities from CERCLA liability through statutory protections that the CERCLA rule did not provide. As stated by NACWA, “The designations (of PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under CERLCA) – finalized without statutory liability protections for the water sector in place and before the imposition of vital source control requirements – are disappointing, and despite EPA’s assertion about settlements they expose public clean water agencies to extensive CERCLA litigation and potential liability for significant costs related to PFAS remediation….. The (EPA enforcement discretion) memo clearly recognizes that it would be inequitable to foist PFAS cleanup costs on clean water agencies. Issuance of a policy on enforcement discretion in conjunction with the rulemaking underscores the extent of concern around who will bear liability for PFAS remediation. However, while the memo is an important, though not legally binding, step, as NACWA has reiterated in several contexts, it can only offer limited protection against suits brought by third parties.”

In addition, the American Water Works Association as a member of the Water Coalition Against PFAS, a coalition of drinking water and wastewater sector organizations, released the following statement, “The Water Coalition Against PFAS believes in holding polluters responsible for cleaning up PFAS and is disappointed that EPA’s designation of PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances will allow them to skirt that responsibility. The final rule from EPA puts water systems at risk, will translate to higher costs for ratepayers, and opens water systems up to costly litigation…. With the rule now finalized, Congress must act immediately to uphold CERCLA’s “polluter pays” principle and provide a statutory liability shield for water systems related to PFAS cleanups.”

Toward that end, members of Congress are acting, and a bill was introduced by Reps. John Curtis (R-UT) and Marie Gluesenkamp Perez (D-WA), The Water Systems PFAS Liability Act (H.R. 7944) is a companion bill to Senate legislation introduced by Sen. Cynthia Lummis (R-WY), last year. The bill provides statutory protection for public water systems, public or private publically owned treatment works (POTWs), municipal stormwater systems, water agencies, and contractors managing or disposing of materials associated with permitted discharges for stormwater and their customers from CERCLA enforcement and litigation. .

Samir Mathur, CDM Smith water reclamation practice leader, is especially concerned for water reclamation facilities and their associated biosolids management programs. "Biosolids offer benefits such as carbon sequestering, low-cost/high-value fertilizer, and a sustainable way of managing nitrogen and phosphorus," Mathur says. "Costs for biosolids management have increased substantially in states like Maine, where there is a moratorium on biosolids land application because of PFAS." In Maine, POTWs have already seen a 300 percent increase in biosolids management cost that is being borne by the ratepayers and not the originators of these chemicals. There is a concern the potential CERCLA liability will have the unintended consequences of prohibiting the beneficial use of biosolids

Currently, no practical and cost-effective technologies remove PFAS from POTW effluent. Absorptive technologies well suited in other industries for PFAS treatment are difficult to cost-effectively apply in typical POTW effluent. If POTWs are forced to utilize these technologies, treating and disposing of the resulting spent media could negatively impact the environment and create new CERCLA liability concerns.

5. More PFAS are now being considered to be added as CERCLA hazardous substances.

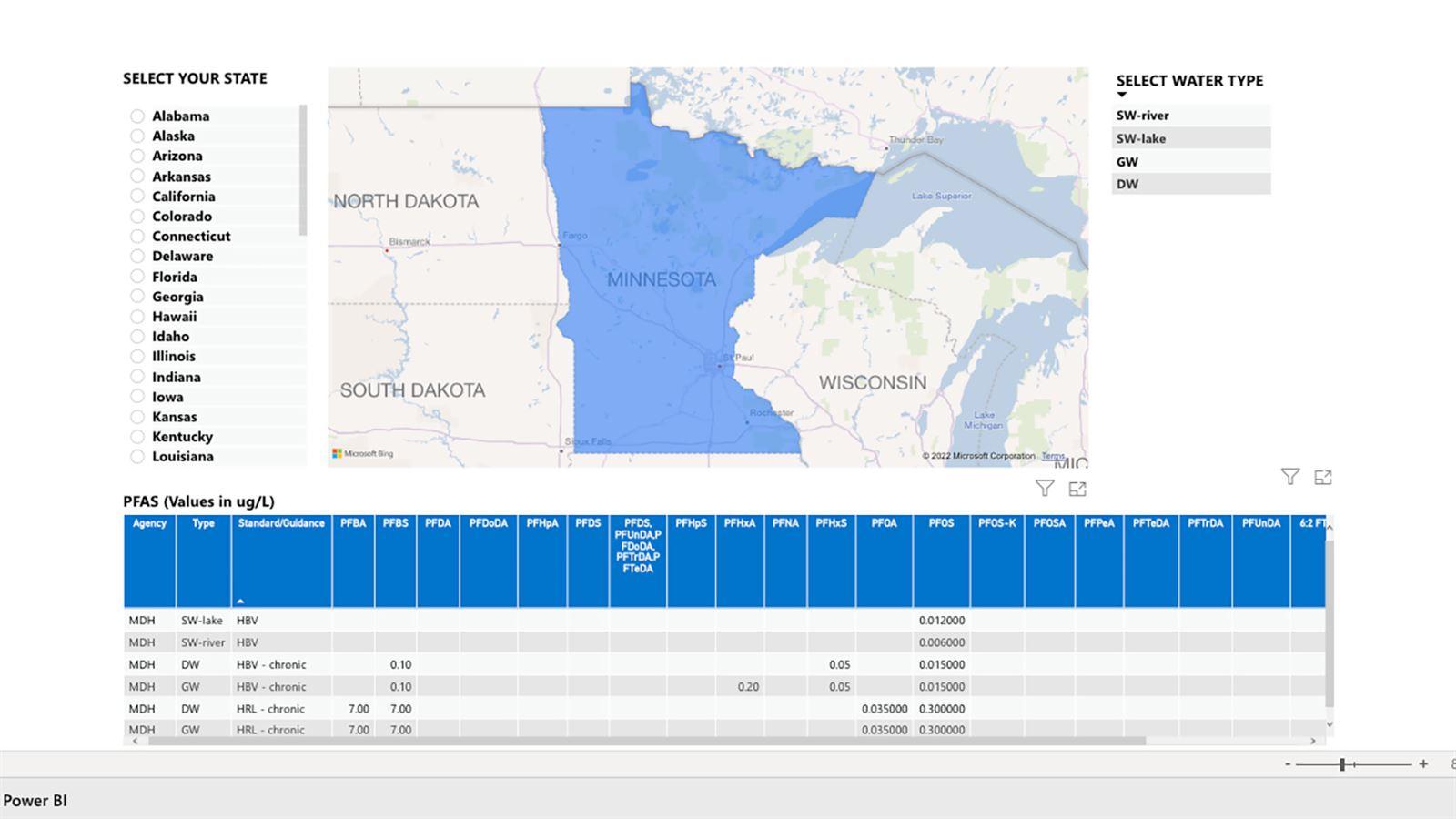

On April 13, 2023, the EPA issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM) to request public input regarding the potential development of future regulations for PFAS under the CERCLA. The Agency is seeking input and data concerning the potential future hazardous substance designation under CERCLA of seven PFAS other than PFOA and PFOS and their salts and structural isomers, or some subset thereof. These seven PFAS include PFBS, PFNA, PFHxS, GenX, PFBA, PFHxA, and PFDA as well as their precursors. Precursors of PFOA and PFOS have also been added. A precursor is a PFAS that can naturally transform into one of these nine PFAS via microbial or abiotic processes. The potential designations for precursors to PFOA, PFOS, the seven PFAS compounds above, opens up CERCLA designations potentially to thousands of additional individual PFAS. There are concerns that the EPA does not provide the industry with a defined list of the specific substances covered under the rule. This could result in companies unintentionally violating CERCLA. Ian Ross, CDM Smiths PFAS practice lead has commented that “precursors to PFOA, PFOS and PFHxS were included in international regulations, under Stockholm convention (since 2009 for PFOS) and the addition of regulatory thresholds for PFOA-precursors in European regulations (220/784) has led to the use of specific chemical analytical methods, such as the total oxidizable precursor assay, which has been used commercially for serveral years to determine if concentrations of PFOA-precursors breach regulatory thresholds, with this approach being applicable to the US to assess precursors and their concentrations.”

In addition, CERCLA’s definition of “hazardous substances” includes any substance designated pursuant to other environmental statutes such as the Clean Water Act, Resource

Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), CAA, and Toxic Substances and Control Act (TSCA). On February 8, 2024, the EPA proposed amending RCRA Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Parts 261 and 271 by adding nine PFAS compounds (including their salts and structural isomers) to the list of RCRA “hazardous constituents”:

- Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

- Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)

- Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS)

- Hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid. (GenX)

- Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)

- Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS)

- Perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA)

- Perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA)

- Perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA)

If finalized, this rule would allow EPA to further investigate and clean up PFAS through the RCRA corrective action process. In addition, any PFAS included in the final rule (e.g., the 7 PFAS in addition to PFOA and PFOS) would also be added as CERCLA hazardous substances.

6. Start a risk management strategy—now!

While legislators and lobbying groups refine the EPA’s proposed rulemaking, there are actions you can take to manage your risk. Reach out to CDM Smith’s roster of renowned PFAS experts for an initial assessment. Our teams are developing comprehensive PFAS strategies, including risk registers to help clients evaluate their regulatory risks, schedule risks, technical risks and cost risks.

Additionally, our team can conceptualize and customize a unique PFAS lifecycle for your site and your community, incorporating PFAS sources, migration routes in the environment, and receptors to develop a comprehensive understanding of PFAS in your environment. We also have expertise in PFAS risk communication and can help develop internal and external (public) strategies around communicating PFAS issues and risks.

Our approach has the potential to leverage synergistic technologies to provide a more sustainable solution for PFAS treatment.